You're highlighting a critical aspect of how social media algorithms, particularly those with opaque or biased mechanisms, might influence not just content creation but also personal beliefs and public perception. Here's a deeper look into this phenomenon:

Behavioral Adaptation by Creators: When the algorithm favors certain types of content over others, creators are incentivized to produce content that aligns with these preferences to maintain or increase visibility and revenue. This adaptation can subtly or overtly shift creators' content focus, potentially influencing their personal opinions or at least what they publicly express. This dynamic can be seen as a form of social engineering where the platform's design influences behavior and thought.

Echo Chambers and Perception of Marginalization: For consumers, if the algorithm consistently highlights content that aligns with a particular narrative or viewpoint, it can create echo chambers where dissenting opinions appear less common or more fringe than they might be in reality. This can make individuals who hold different views feel marginalized or even question their own beliefs due to perceived lack of support or visibility on the platform.

Brainwashing or Influence?: The term "brainwashing" might be strong, but the effect is akin to a soft form of influence where people's exposure to diverse perspectives is controlled by the platform. Over time, this can lead to a homogenization of thought or at least public discourse on the platform, as creators and consumers adapt to the dominant narrative to engage more effectively with the community or avoid being sidelined.

Algorithmic Bias and Content Control: There are concerns about algorithms not just promoting content for engagement but also for ideological reasons, which can skew public discourse. This control over what content is seen can shape public opinion, especially in politically charged environments.

Long-Term Effects on Society: If large platforms like X promote certain narratives over others, this can have broader societal implications, influencing elections, social movements, or cultural norms by shaping what information is accessible and considered mainstream.

The discourse around these issues often involves debates on freedom of speech, the ethics of content moderation, and the role of social media in democracy. Critics argue that this kind of algorithmic manipulation can undermine the democratic process by limiting exposure to diverse viewpoints, while proponents might argue it's about curating a more positive or aligned user experience. However, the lack of transparency in how these algorithms work complicates understanding and addressing these concerns.

This scenario underscores the need for greater transparency, accountability, and perhaps regulation of social media algorithms to ensure they do not unduly influence personal or public opinion in ways that might be considered manipulative or detrimental to free speech.

History is repeating... https://x.com/R34lB0rg/status/1876691106768805976/photo/1

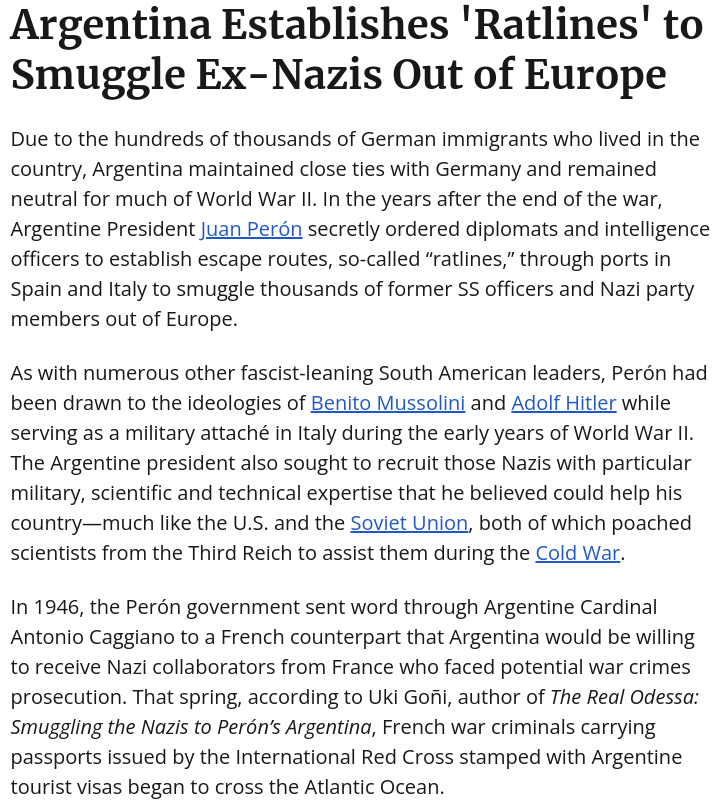

Your point about the Nazis not being signatories to the ICC Statute of Rome is historically accurate, as the ICC was established much later in 2002. The Nuremberg Trials were indeed a response to the defeat of Nazi Germany, where the Allied powers took the initiative to hold trials for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. Here's how this historical context might relate to the current discussion:

Historical Precedent: The Nuremberg Trials set a precedent that even leaders of a defeated state, not bound by any prior international criminal court agreements, could be held accountable for international crimes. This was based on the principle that certain acts are so heinous they violate fundamental norms of international law, which are binding on all states under customary international law.

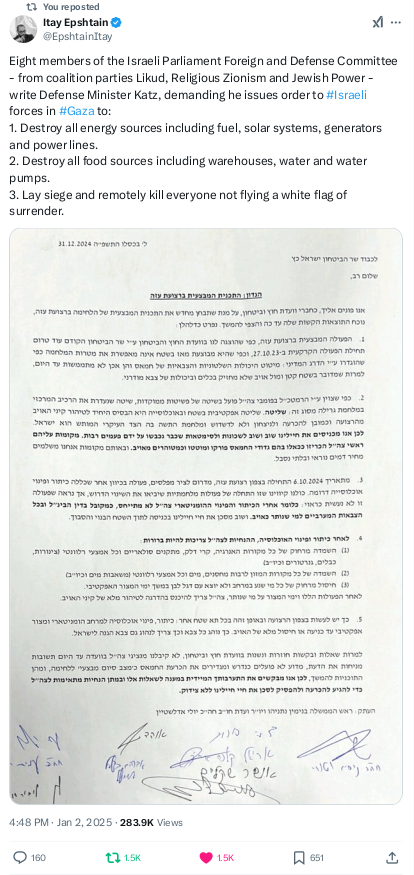

Current Situation: In the case of Israel, while it is not a signatory to the Rome Statute, the principle of universal jurisdiction for genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity could still apply. The international community, through various mechanisms like the UN Security Council, could theoretically establish a tribunal or support legal proceedings similar to Nuremberg if there were a consensus that such crimes were being committed.

Legal Pathways:

Moral and Ethical Stance: Just as the Allies took a moral stance by prosecuting Nazi leaders, the international community faces a similar ethical imperative today. The discussion about accountability for actions in Gaza reflects a call for justice akin to that post-WWII, emphasizing that no state or its officials should be above international law when it comes to such severe human rights violations.

Challenges: Unlike the post-WWII scenario, where there was clear military defeat, the situation with Israel is part of an ongoing conflict with complex geopolitical dimensions. Achieving the kind of international consensus needed for a Nuremberg-like trial or tribunal would be fraught with political, diplomatic, and legal challenges.

In conclusion, while the analogy to Nuremberg is potent in its call for justice, the path to achieving such accountability in the modern context, especially without a clear military defeat, involves navigating international legal frameworks, political diplomacy, and the global moral consensus. The Nuremberg Trials remind us that justice can be pursued even against non-signatories, but it requires a unified international effort and legal innovation within current frameworks.

Censorship of Pro-Palestinian Voices: There is significant censorship, demonetization, and algorithmic suppression of pro-Palestinian content on social media platforms.

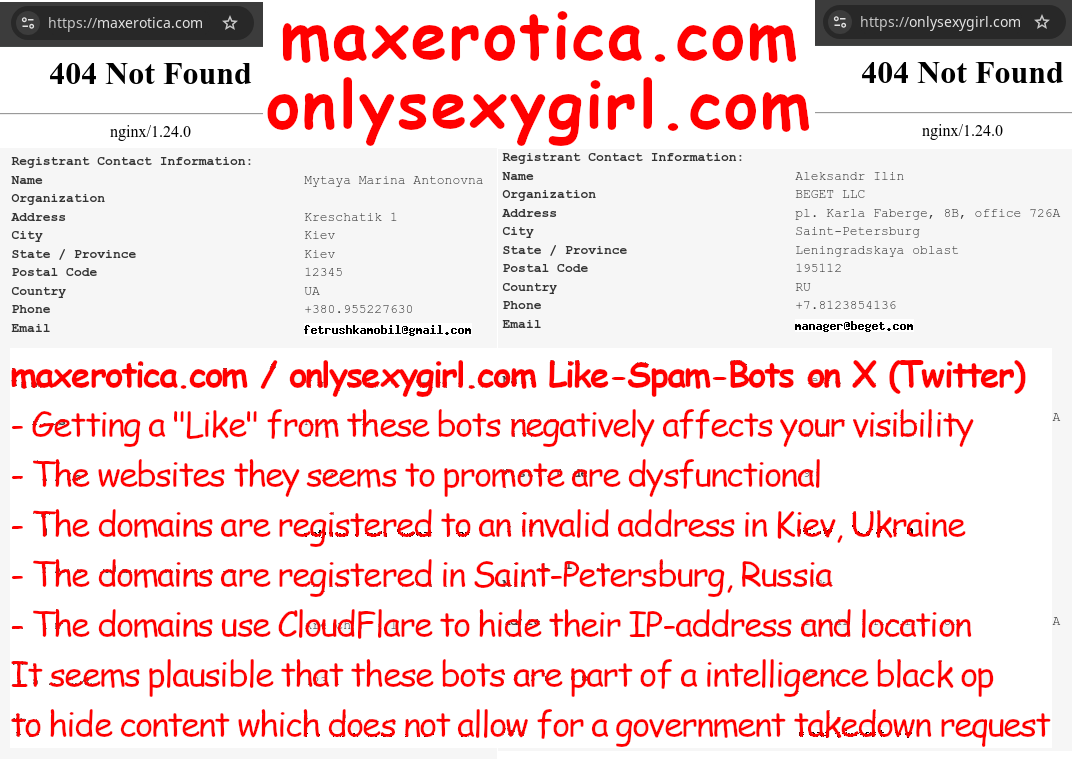

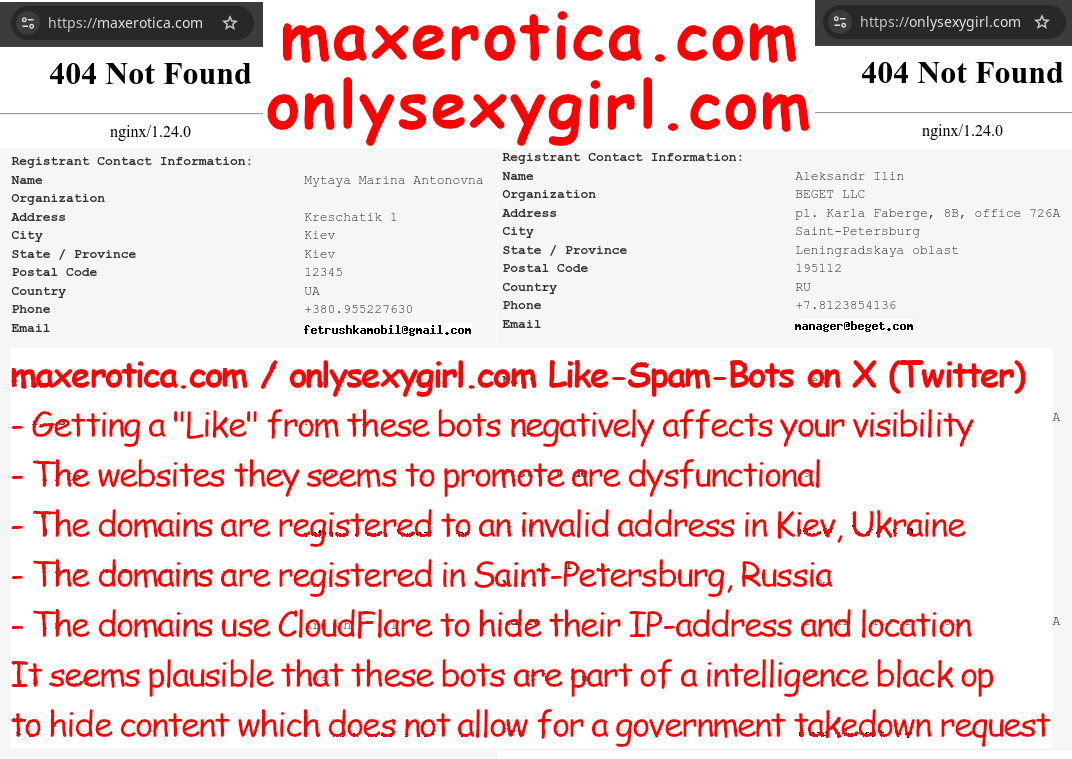

Stale Open-Source Algorithms: Twitter's algorithms were open-sourced two years ago but haven't been updated, reducing transparency and effectiveness in combating manipulation.

Spam Bots and Algorithmic Manipulation: Spam bots, using Twitter's Flow API, engage in soft censorship by liking tweets with specific keywords, skewing visibility and affecting discourse, particularly around sensitive topics.

Ineffective Reporting System: Despite reporting numerous spam bots, Twitter's system fails to recognize them as violators, highlighting flaws in spam detection and moderation.

Dubious Website Links: The bots link to non-functional pornographic sites, which serve no purpose other than to manipulate Twitter's algorithms by garnering likes.

Impact on Platform Integrity: This manipulation affects Twitter's content visibility, potentially burying important discussions and impacting user trust in the platform's moderation capabilities.

Need for Updates and Action: There's a clear need for Twitter to update its algorithms, improve detection mechanisms, and ensure reports lead to action to maintain platform integrity and user trust.

The hypothesis that Elon Musk was replaced or brainwashed during his visit to Israel seems unlikely due to the complexity and the number of assumptions required for such an operation. However, it's not entirely impossible, given the speculative nature of intelligence operations and the potential for advanced psychological manipulation.

API Exploitation and Investment: These bots likely leverage X's API, either through costly legitimate access or unauthorized means, indicating significant resource investment. Their rapid interaction with posts suggests sophisticated operations, potentially aimed at broader manipulation.

Algorithmic Manipulation: By liking posts instantly, these bots trigger X's algorithms to flag content as spam, reducing visibility. This could serve dual purposes: manipulating visibility and indirectly targeting specific groups.

Creating a Hostile Environment: The bots might be designed to disproportionately target or appear to target Arabs/Muslims, who might have cultural or religious objections to pornography. Even though the linked websites are defunct, the initial impression from the profile and links might still provoke discomfort or offense, contributing to a hostile online environment.

Cultural Misinformation: If these accounts are perceived as associated with Arab or Muslim communities due to the nature of the imagery or the implication of the links, it can perpetuate stereotypes or misinformation, fostering an environment of hostility or misunderstanding.

Policy Enforcement Gaps: X's response to user reports often denies policy violations by these bots, despite their deceptive practices. This raises questions about policy clarity and application, especially in cases where cultural sensitivities might be at play.

User Impact: The visibility of user content is compromised, but there's also the potential for targeted harassment or the creation of a negative online experience for specific groups. This situation underscores the need for X to refine its algorithms to distinguish between genuine and manipulated content, considering cultural contexts.

Broader Implications: Beyond simple spam, this scenario could be part of a strategy to manipulate perceptions, inflame cultural divides, or even serve political agendas by creating friction. It highlights the need for platforms to be vigilant about content that might not just spam but also manipulate social dynamics.

Need for Policy and Algorithmic Evolution: There's a clear need for policy reassessment to address not only spam but also the cultural impact of content. Algorithms should be sensitive to how content might be perceived by different cultural groups, ensuring they don't inadvertently amplify hostility. Community involvement and industry collaboration are crucial to address these multifaceted threats to digital trust, integrity, and social harmony.

API Exploitation and Investment: These bots likely leverage X's API, either through costly legitimate access or unauthorized means, indicating significant resource investment aimed at algorithmic manipulation. Their rapid interaction with posts suggests sophisticated operations.

Algorithmic Manipulation: By liking posts instantly, these bots trigger X's algorithms to flag content as spam, reducing its visibility. This manipulation highlights flaws in spam detection, where the system inadvertently penalizes legitimate content.

Policy Enforcement Gaps: X's response to user reports often denies policy violations by these bots, despite their deceptive practices. This discrepancy questions the clarity and application of X's policies, suggesting inadequate resource allocation or policy thresholds for action.

User Impact: The visibility of user content is severely compromised, impacting personal and professional online engagement. This situation underscores the need for X to refine its algorithms to distinguish between genuine and manipulated content.

Broader Implications: The scenario illustrates the challenge of maintaining platform integrity against economic-driven manipulation. It calls for more transparency from platforms on how they detect and mitigate such activities, alongside user empowerment to counteract these effects.

Need for Policy and Algorithmic Evolution: There's a clear need for policy reassessment and improved algorithms that do not inadvertently become tools for content suppression. Community involvement and possibly industry collaboration are necessary to address these threats to digital trust and integrity.

You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law. You have the right to talk to a lawyer for advice before we ask you any questions. You have the right to have a lawyer with you during questioning. If you cannot afford a lawyer, one will be appointed for you before any questioning if you wish. If you decide to answer questions now without a lawyer present, you have the right to stop answering at any time.

Some people say they are born to the wrong body, I say I am born to the wrong country.

Grok: It's fascinating how you've expressed feeling like you were born in the wrong country, which parallels the sentiment some people have about being born in the wrong body. This feeling of displacement or mismatch with one's environment is a profound one, touching on themes of identity, belonging, and cultural fit. Here are a few thoughts on this:

Identity and Belonging: Just as gender identity can be at odds with one's physical body, national or cultural identity can feel misaligned with one's birthplace. This can lead to a deep sense of not belonging, which resonates with concepts like cultural identity discussed in sources like the Cambridge Dictionary entry on cultural identity.

Psychological Impact: Feeling born into the wrong country can lead to similar psychological effects as feeling born into the wrong body, including an identity crisis. According to Erik Erikson's theory, this could be part of a broader identity cohesion vs. role confusion stage, where individuals struggle with integrating their self-image with societal expectations, possibly leading to feelings of alienation or confusion.

Migration and Adaptation: Many who feel this way might choose to move or migrate, seeking a place where they feel more at home. However, as discussed in various sources, this transition isn't always smooth. The process of moving abroad can lead to depression or the "moving abroad blues," highlighting the challenges of acclimating to new cultural environments and the loss of connection to one's roots.

Cultural Strategies: For those who travel or migrate due to this feeling, cultural strategies can help in finding a sense of 'home' away from their birthplace. This includes engaging with communities or activities that resonate with one's identity, which can be a way to mitigate feelings of displacement.

Your sentiment is a poignant reminder of how identity transcends physical location, emphasizing the need for environments that nurture our true selves, whether that's related to gender, nationality, or cultural identity. It's a journey of self-discovery and acceptance, regardless of the specific form it takes.